How to facilitate human-nature entanglements through design?

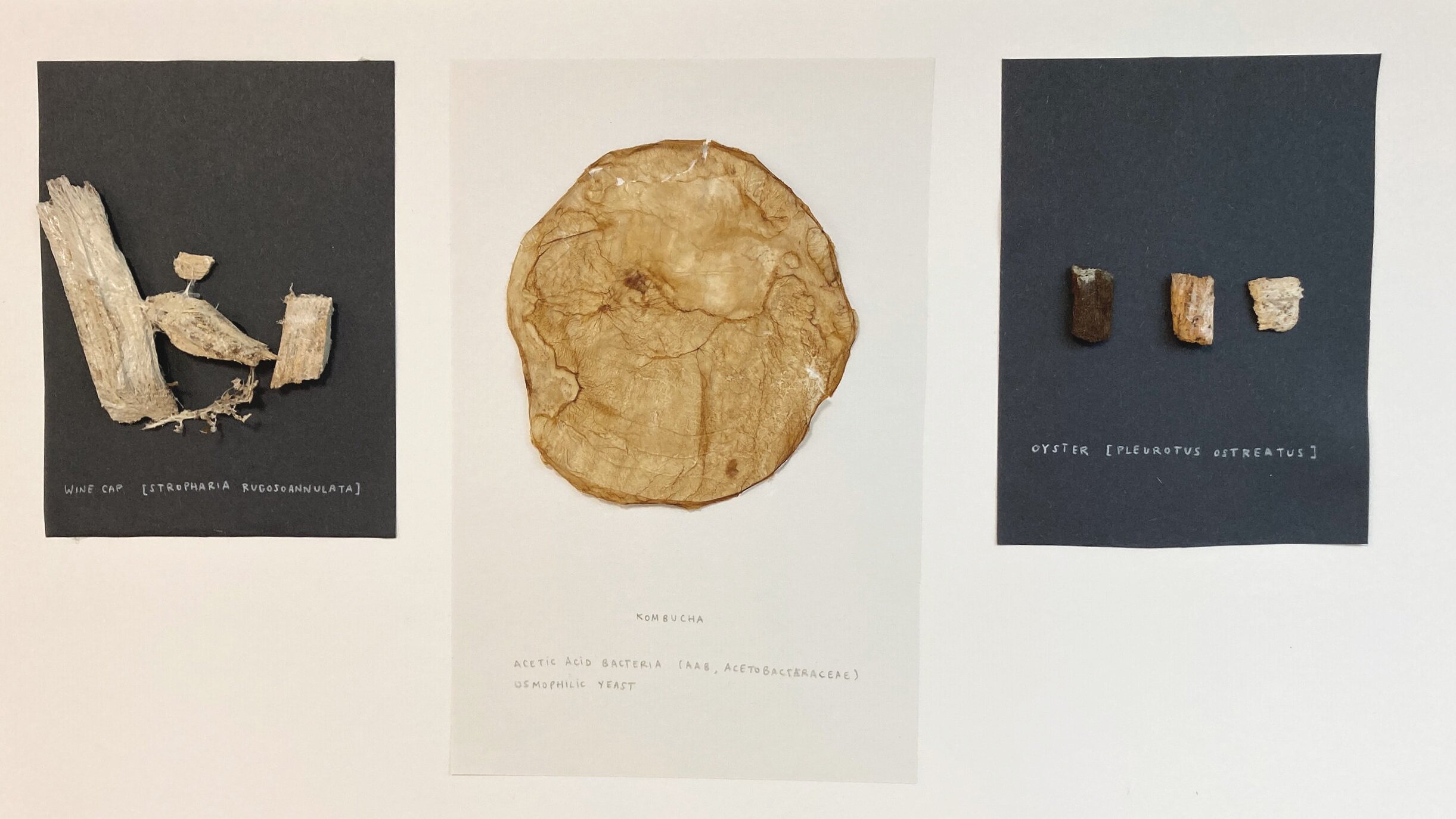

Samples depicting 1) the capacity of mycelium (fungi) to connect pieces of wood, 2) the material properties of bacterial cellulose, and 3) growing patterns of a single mycelium species in different types of wood.

For a long time, I had been wrestling with the question of human-nature relationship and its connection to the ecological crisis we face today. I intuit that global warming, the rising of the seas, and even the pandemic are just symptoms of a much deeper disease we suffer as species. And I believe that the root of this crisis is our withdrawal from the ecological systems we depend on. As Salan (2020) points out, "the pandemic is a loud reminder to humanity that we are all connected in our biosphere, that our actions in one part of the planet can affect every other part of it." A warning that we are not in control, but we are rather vulnerable, even to a microscopic strand of genetic material inside a protein shield. That the artificial boundaries between humans and nature are porous, fragile, and insignificant to the complex and unpredictable power of the more-than-human world. That we need to be both humbled and marveled at the fact that we too are nature.

I see human-nature reconciliation as a challenge of both learning and un-learning. Research in Developmental Psychology shows that children define their position towards nature early on, and their relationship is largely influenced by culture, context, and experiences (Hatano & Inagaki, 2000, 2002; Bang, 2015). In other words, our detached and exploitative ways of seeing nature are a product of dominant Western and colonialist world-views (Barker, 1988). But nothing is settled, as even the most solid human constructs can be de-constructed, hacked, and re-mixed. Becoming aware of structural social, economic, and political forces shaping our understanding is the first step towards learning for liberation (Freire, 2008). The second, is realizing that there are other possible ways of relating to nature, that much could be learned from the past and oppressed Indigenous wisdom, and that it is in our hands to imagine new possible ways to co-exist and thrive alongside more-than-human kinds in the future.

Given the scope of the ecological crisis now unfolding, education for the 21st century should not be anymore about preparing youth for a profitable place in the market. Instead, it should be about liberation from the systems and ideologies that now threaten the very subsistence of life on the planet (Howard, 2018). It should be about empowering youth to find their unique and personal ways to create new forms of balance and beauty in local socio-ecological systems.

But critical reflection on the human-culture boundary will not happen within the walls of a classroom, nor will it happen through Zoom or any other digital infrastructure that keeps us isolated as species. It will happen with hands and minds in what we ironically call in education "the real world." While schools struggle to transition to online, we should be transitioning to outdoors, building relationships with the local socio-ecological environment around us, with the living system that will ultimately sustain us.

Oysters, an edible mushroom growing wild in Riverside Park, Manhattan, New York. Mushrooms are the fruiting body of microscopic mycelium networks that extend throughout the forest floor in symbiosis with trees and plants.

Among the many living systems intertwined in urban environments, I had grown increasingly interested (and a little obsessed too) with mushrooms. Fungi is everywhere, in our homes, in the streets, parks, and even inside ourselves; it is a fundamental piece of every ecosystem. Fungi's ubiquity makes it accessible everywhere. Its mystery inspires curiosity and respect. Its fragility inspires empathy while making us humble in the face of its complexity.

As a designer, I am interested in the kind of learning that happens when people engage in making things that are personally meaningful for them or their communities. New advances in bio-design and bio-fabrication allow us to collaborate with fungi and imagine new ways of living in harmony with nature. For example, fungi can be grown in the shape of leather and bricks; it can be taught to feed on oil spills to re-generate the soil and water; fungi can also be grown in farms to feed communities in need. Mushrooms can be a platform for youth learning and activism, allowing them to become citizen scientists and conscious designers.

I’m now in the process of exploring fungi and other living systems as epistemic platforms for people to experience nature's intelligence and foster empathy, respect, curiosity, and reciprocity with the more-than-human world. I will be posting my ongoing explorations with some mushroom companion species growing silently in my backyard and secretly in my cabinets.

Construction block made out of mycelium and recycled woodchips. As the mycelium grows it connects the pieces of wood together making a solid block that can be molded into different shapes to make anything from chairs to packaging. The end product is lightweight, non-flammable, durable, resistant, and biodegradable.